The Big Meadow Search (BMS) started out in 2021 as a modest project just for our county, to get more of an idea of which plants were in grassland on our members’ land. It arose from a discussion in the CMG steering group about the various existing plant monitoring schemes, in which a specific quadrat or area is examined, and the plants within it are identified and their cover assessed. This is a valuable technique for measuring changes over time; but it doesn’t really tell you what is in the whole field, and it’s hard to pick a “typical” area, as parts of the field may differ in, for example, how wet they are which will affect what grows there.

So, the idea of the BMS was a much less formal way of just having a wander round an area of grassland, and noting down whatever plants you see and are able to identify. A very informal way of doing things; but as soon as it started it was generating new records of plants at sites where they hadn’t been recorded before. Initially, it was just going to be during one week, but it seemed sensible to extend the BMS period to the whole of June, July and August. It also generated interest outside of Carmarthenshire, and Wales, so it was decided to make it a UK wide project. Funding was provided by CMG and the West Wales Biodiversity Information Centre (WWBIC) to develop a website, and we had flyers printed to distribute to any organisations or individuals we thought might be interested.

Since this modest start, BMS has generated a lot of records of grassland plants, over 20,000 at the end of the 2023 search period, from Cornwall to Scotland, Ireland to East Anglia, and even from the Channel; Islands. BMS-ers can now enter their result directly onto the website, and the records are all passed on to the Environmental Records Centre for the appropriate area. The project has done what it set out to do – to encourage people to record the plants they find in an area of grassland; but that isn’t the only outcome.

Many people are put off this kind of project because they feel they don’t have the necessary expertise to identify many plant species with confidence. I certainly felt that myself initially. I’m no botanist, and wondered whether there was any point in someone lacking botanical expertise taking part. But records of common, easily identifiable species are just as important as those of rarities, and if you go out and have a good look at plants you are certainly going to be increasing your botanical knowledge. Even if you can’t name everything you see, you will become much more adept at recognising which family an unknown plant belongs to so you can look it up in a field guide.

A BMS Facebook group was created, which now has even more members (611 at the time of writing) than the highly successful CMG one. It, and its equivalent Twitter or “X” feed (now with 2887 followers), are supplied with daily updates and posts on plants ID, and associations between the plants and invertebrates, galls, and fungi. It is very unusual to see all these associations highlighted in one place, and the first series of these posts have been collected into the BMS book:

(there is a handful of copies left for sale!).

When going out to do a BMS, I find it helpful to take a few books along in my rucksack, although it’s often easier to take detailed photos of plants you’re unsure about, and look them up at home later. The cameras on smartphones are very suitable for this, and inexpensive macro attachments enable very detailed close-ups. There is excellent advice on how to photograph plants to aid ID on the BMS website here:

https://www.bigmeadowsearch.co.uk/get-involved

Smartphones also enable the use of apps in which artificial intelligence is applied to many areas of biological identification; Plantlife reviewed ten of the botanical ones recently. Their top choice was a free app called “Flora Incognita”, which I have found helpful. It gives a level of certainty on its decision, so I find this app useful – with the major caveat that the common names it gives to some plants are not at all what you would expect (for example it calls Herb Robert “Stinky Bob”), so it’s essential that you check its ID decisions yourself in your books using the scientific name of the plant rather than the common name.

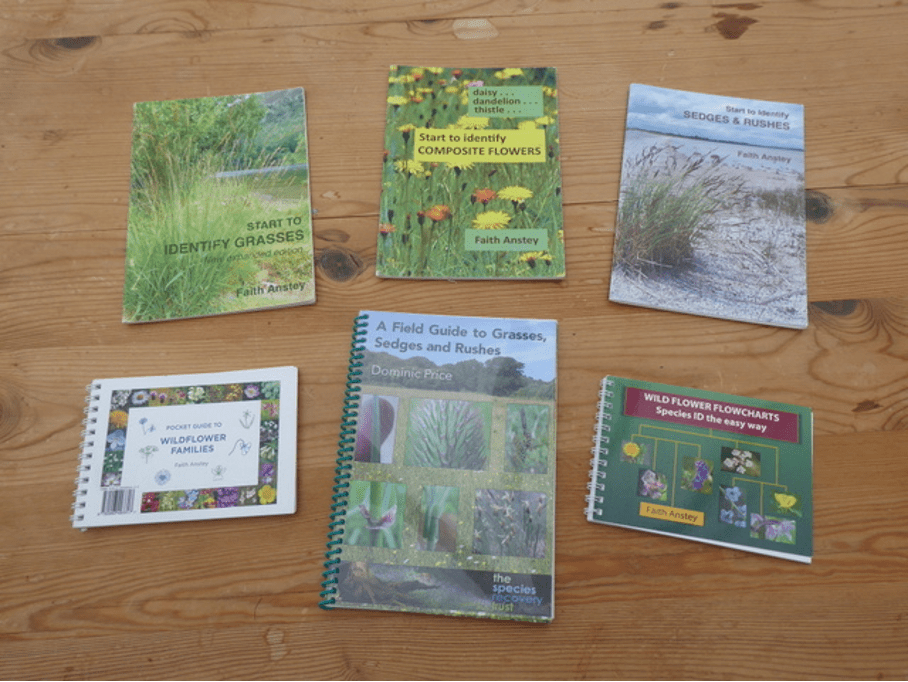

There are lots of excellent ID guides; here are a few:

And the Field Studies Council publish these inexpensive guides which contain very helpful ID points:

But it’s not necessary to bust a gut trying to identify difficult plants if you haven’t yet got the knowledge or the experience needed, I certainly don’t! Just record what you know, and if you can’t decide which sedge or rush or grass it is you’re looking at with furrowed brow, leave it and move onto something else. The absence of that record at your site doesn’t reduce the value of the other records you have made.

I’ve been having some nice half-days out visiting lovely stretches of Coast Path, interesting road verges, woodland rides, churchyards, and other grassy areas for the last four years of summers, doing BMS’s. We’re just about at the end of July, there is still the whole of August left, so why not get outside in the fresh air, go for a wander around an area of grassland (get permission first if it’s not public access!!!!!) and have a closer look at what you are walking through.

Finally, the Steering Group would like to express our thanks to one of our number, Laura Moss. As well as helping to run CMG, Laura works for two Biological Records Centres, and she has put countless hours of work into designing and running the Big Meadow Search, and producing the social media posts. The project would not exist without her many ideas and tireless effort.